@. Ampère et l'histoire de l'électricité |

[Accueil] [Plan du site] | ||||||

Une nouvelle plateforme est en cours de construction, avec de nouveaux documents et de nouvelles fonctionnalités, et dans laquelle les dysfonctionnements de la plateforme actuelle seront corrigés. |

|

||||||

Parcours historique > Des lois pour le courant : Ampère, Ohm et quelques autres... | |||||||

Faraday, Ampere, and the mystery of continuous rotations Français Français

By Christine Blondel and Bertrand Wolff

On returning from his inspection tour during the summer of 1821, Ampere had somewhat forgotten electromagnetism. Faraday's memoir relaunched his researches. "This memoir contains very singular electromagnetic facts that confirm perfectly my theory, although the author tries to contest it by substituting one of his own invention." Additionally, Ampere thought that these continuous rotations produced, to his great astonishment, the permanent production of a vis viva [in modern terms, kinetic energy] capable of overcoming friction without any expenditure of work. How can one explain such an apparently "free" production of motion? And what was the nature of the theoretical opposition between the two physicists? Ampere provisionally put aside the first question, but straight away returned to Faraday's experiments and sought to integrate them into his theory.

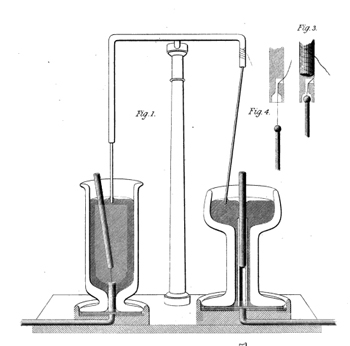

Faraday: "I wait for further proofs"To explain the continuous rotations involving magnets, Ampere called on his hypothesis of the existence of electric currents inside magnets. From his formula that gives the force acting between two current elements, it is indeed possible, at least theoretically, to "submit the phenomena to calculations" [See the page In Search of a Newtonian Law of Electrodynamics]. The rotation of a conductor around the pole of a magnet, or vice versa, thus appears for Ampere as a composite result arising from a multitude of elementary actions. For Faraday, in contrast, it was the rotation itself that constituted the "primary fact", while the hypothesis of currents in magnets seemed to him to be superfluous and risky. "I am naturally skeptical in the matter of theories and therefore you must not be angry with me for not admitting the one you have advanced immediately. The ingenuity and applications are astonishing and exact, but I cannot comprehend how the currents are produced and particularly if they be supposed to exist round each atom or particle and I wait for further proofs of their existence before I finally admit them." (2 February 1822) See the letter] The rotation of a current under the action of a current obtained by Ampere was not enough to change Faraday's opinion. For the latter, it was the attraction and repulsion between currents that must be considered as composite facts resulting from a combination of rotational actions. However, he did not pursue the debate, attenuating his disagreement with the mention of his "deficiency in mathematical knowledge" and his weakness in the domain of theory. "On reading your papers and letters, I have no difficulty on following the reasoning, but still at last I seem to want something more on which to steady the conclusions. I fancy the habit I got into of attending too closely to experiment has somewhat fettered my power of reasoning and chains me down [...]. With regard to electromagnetism also feeling my insufficiency to reason as you do, I am afraid to receive at once the conclusions you come to (though I am strongly tempted by their simplicity and beauty to adopt them) [...] It delays not because I think them hasty or erroneous, but because I want some facts to help me on." (3 September 1822) See the letter] Perpetual motion from electricity?The candidate experiments for the title of ancestor of the electric motor are not lacking. [See the page Did Ampere invent the galvanometer . . . the electric motor?]. Don't Faraday's continuous rotation experiments show the possibility of using electromagnetic force to product a continuous rotational motion? Nonetheless, it was the theoretical implications, not an eventual motor application, that aroused the interest of Ampere and his contemporaries. First of all, the continuous rotations furnished Ampere with an argument that to him seemed decisive against the electromagnetic theories resting, like that of Biot, on the magnetization of the conductors. Indeed, it is impossible to obtain these continuous rotations only with magnets. In addition, one aspect of Ampere's and Faraday's experiments aroused great astonishment among theorists. As we have seen, Ampere believed that he saw in them a free production of vis viva [kinetic energy]. This is what he expressed in his Exposé sommaire that he read at the public meeting of the Academy of Sciences on 8 April 1822: "A movement that continues always in the same direction, despite friction, despite resistance from the environment, and [...] produced by the mutual action of two bodies that remain constantly in the same state, is a fact without precedent in all that we know of the properties that inorganic matter can exhibit." A movement produced by the mutual action of two bodies remaining in the same state: is that not the definition of perpetual motion, even if one dares not utter the term? Such motion obtained without the expenditure of work is certainly a "fact without precedent" that the Academy of Sciences refused to take into consideration since 1775! The phenomenon no longer astonishes us as it amazed Ampere and his contemporaries, because we take into account the principle of the conservation of energy formulated in the middle of the nineteenth century. Chemical transformations occur within the battery, and these convert chemical energy into electrical energy. With the rotation of the moveable circuit, this electrical energy is converted into mechanical energy. For his part, taking into account the fact that electricity at rest had never caused this type of phenomenon, Ampere advanced the hypothesis according to which "one cannot attribute this action [responsible for continuous rotation] but to fluids in motion."

Further readingsFaraday, Michael. Faraday's Experimental Researches in Electricity: Guide to a First Reading, ed. by Howard J. Fisher. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Green Lion Press, 2001. Locqueneux, Robert. Ampère, encyclopédiste et métaphysicien. Paris, Lille: USTL, 2008. Hofmann, James R. André-Marie Ampère. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Blondel, Christine. André-Marie Ampère et la création de l'électrodynamique, 1820-1827. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, 1982. A bibliography of "secondary sources" on the history of electricity. French version: June 2009 (English translation: March 2014)

|

|||||||

|

© 2005 CRHST/CNRS, conditions d'utilisation.

Directeur de publication :

Christine Blondel. Responsable des développements informatiques : Stéphane Pouyllau ; hébergement Huma-Num-CNRS |